T+1 question: Is speed overlooking mechanisms designed to protect the consumer

7 min read

The Balancing Act: T+1 Settlements, Affirmation Rates, and the Complexity of Multi-Party Transactions

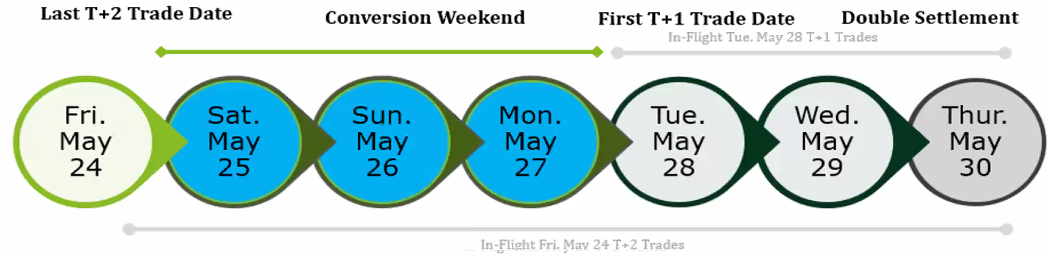

Beneath the surface of T+1 seemingly straightforward improvements lies a complex ecosystem of executing brokers, clearing firms, and custodians, each playing a critical role in the lifecycle of a trade. This complexity, especially in scenarios involving Delivery Versus Payment (DVP) and Prime Brokerage, raises essential questions about the operational and regulatory checks in place to safeguard customer interests and ensure market transparency.

The AML Oversight in the Race to Affirmation

In transactions where trades are executed, cleared, and settled by different entities, a robust check and balance system becomes paramount. This system ensures proper account instruction setup, accurate settlement instructions, and guards against regulatory infringements like free riding and naked short selling. But as we inch closer to the T+1 horizon, a pressing concern emerges: with the operational sprint towards affirmation and settlement, is there a risk of sidelining critical anti-money laundering (AML) checks and customer protection mechanisms?

The push for rapid affirmation—verifying the accuracy of trade details before moving to settlement—introduces a potential blind spot in AML vigilance. While each participant in the trade lifecycle bears a slice of the responsibility pie—from executing brokers conducting KYC procedures to banks transferring funds—there’s an overarching need for a cohesive strategy that doesn’t compromise on AML diligence for the sake of speed.

The Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation (DTCC) stands at the forefront of this transition, advocating for higher affirmation rates to facilitate T+1 settlements. The logic is sound: a faster affirmation process underpins the efficiency of T+1 settlements, ensuring trades are known and accounted for in a timely manner. However, this raises an existential question for the markets: in our pursuit of speed and efficiency, are we at risk of overlooking the very mechanisms designed to protect the consumer and maintain trust in the financial system?

The Delicate Dance of Speed vs. Safety

As the financial industry grapples with these challenges, it’s clear that the path to T+1 is not just a technical upgrade but a philosophical pivot. The balance between speed and safety, efficiency and oversight, requires a nuanced approach. It calls for enhanced technologies that can handle rapid affirmation without bypassing essential checks, regulatory frameworks that adapt to the new pace without diluting standards, and a culture of vigilance that prioritizes integrity over expediency.

As the financial industry grapples with these challenges, it’s clear that the path to T+1 is not just a technical upgrade but a philosophical pivot. The balance between speed and safety, efficiency and oversight, requires a nuanced approach. It calls for enhanced technologies that can handle rapid affirmation without bypassing essential checks, regulatory frameworks that adapt to the new pace without diluting standards, and a culture of vigilance that prioritizes integrity over expediency.

When a trade involves multiple parties like an executing broker, a clearing broker, and a custodian broker, several risks emerge, largely due to the complexity and the number of intermediaries. Here are the primary risks associated with such arrangements:

- Counterparty Risk: This occurs when one party in the transaction (for example, the executing or clearing broker) fails to meet their obligations. This can lead to significant losses, especially if the defaulting party is responsible for a large volume of transactions.

- Operational Risk: The involvement of multiple parties increases the complexity of the trade process, raising the likelihood of errors in trade execution, settlement, and reconciliation. These errors can be due to system failures, human error, or process inefficiencies.

- Settlement Risk: Given the delay between trade execution and settlement, there’s a risk that the security’s value could change unfavorably, or one of the parties could default during this period. The more intermediaries involved, the greater the potential delay and, thus, the risk.

- Liquidity Risk: If the clearing broker faces liquidity issues, it might not be able to fulfill its obligations on time. This can delay the settlement process, affecting the liquidity of the executing party or the client.

- Regulatory and Compliance Risk: Different brokers operating in various jurisdictions may be subject to different regulations. Compliance with these varying regulations can be complex and costly, and non-compliance can lead to legal and financial penalties.

- Credit Risk: This is related to the creditworthiness of the clearing and executing brokers. There’s a risk that they might not be able to fulfill their financial obligations due to financial distress.

- Custodial Risk: Custodial risk refers to the risk of loss of securities held by a custodian, either due to the custodian’s insolvency, mismanagement, or fraudulent activities. This risk is heightened when securities are held in a different jurisdiction or in electronic form, where ownership might be less clear-cut.

- Market Risk: The time it takes for the trade to be executed, cleared, and finally settled might expose the parties to adverse movements in the market, affecting the value of the traded securities.

- Intermediary Risk: The failure of any intermediary (executing, clearing, or custodian broker) due to operational, financial, or legal issues can disrupt the transaction process, potentially causing financial loss or delays in trade settlement.

To mitigate these risks, parties involved in such transactions typically conduct thorough due diligence on their counterparties, use trusted and well-regulated brokers, and implement robust risk management and operational control systems. Additionally, central clearing parties (CCPs) are often used in the clearing process to reduce counterparty risk by guaranteeing the trade will settle as expected.

When market participants push for affirmation (the process of confirming trade details before they move to settlement), the responsibility for guarding against Anti-Money Laundering (AML) doesn’t rest with just one entity. Instead, it is a collective responsibility, with various safeguards and protocols in place across different levels of the financial ecosystem. Here’s how AML efforts are distributed among the different stakeholders:

When market participants push for affirmation (the process of confirming trade details before they move to settlement), the responsibility for guarding against Anti-Money Laundering (AML) doesn’t rest with just one entity. Instead, it is a collective responsibility, with various safeguards and protocols in place across different levels of the financial ecosystem. Here’s how AML efforts are distributed among the different stakeholders:

- Executing Brokers: These firms are responsible for ensuring that their clients’ transactions are legitimate and not intended for money laundering. They do this by conducting thorough Know Your Customer (KYC) procedures, monitoring transactions for suspicious activities, and reporting any unusual patterns to the relevant authorities.

- Clearing Brokers: Although their role is more focused on ensuring the smooth settlement of transactions, clearing brokers also have AML obligations. They must verify that the executing brokers they work with comply with AML regulations and that the source of funds for trades is legitimate.

- Custodian Brokers: Custodians, who hold securities on behalf of clients, must also conduct due diligence to ensure that the assets under their management are not the proceeds of crime. This includes AML checks and ongoing monitoring of the securities they hold.

- Regulatory Bodies and Financial Intelligence Units (FIUs): National and international regulatory bodies set the AML standards and guidelines that financial institutions must follow. Financial Intelligence Units in various countries collect and analyze information about suspicious transactions and can initiate investigations or direct financial institutions to take certain actions.

- Central Securities Depositories (CSDs) and Central Counterparties (CCPs): While their primary roles are in the settlement and clearing of trades, respectively, these entities also have frameworks in place to ensure that they are not used as vehicles for money laundering. They achieve this by requiring their members to adhere to strict AML standards.

- Financial Institutions and Banks: Banks involved in transferring funds for trade settlements are required to have robust AML processes, including transaction monitoring systems and reporting mechanisms for suspicious activities.

Each of these participants must comply with AML regulations relevant to their jurisdiction, such as the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) in the United States, the Fourth Anti-Money Laundering Directive (AMLD4) in the European Union, and recommendations from the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) globally. Compliance includes establishing internal policies, procedures, and controls; customer due diligence (CDD) and enhanced due diligence (EDD) for higher-risk clients; ongoing monitoring; and reporting suspicious activities to the appropriate authorities.

The overarching goal is to create a multi-layered defense against money laundering, ensuring that no part of the financial system can be easily exploited for illicit purposes.

A Look Ahead: Embracing Change with Caution

The transition to T+1 settlements is not just an inevitability but a necessity in a world where financial transactions move at the speed of light. However, this transition must be navigated with a keen awareness of the intricate dance between operational efficiency and regulatory compliance. As the financial ecosystem evolves, so too must our approaches to safeguarding the market’s integrity. By fostering innovation in compliance technologies and strengthening collaborative oversight mechanisms, we can ensure that the move to T+1 enriches the market, enhancing both its velocity and its virtue.

The transition to T+1 settlements is not just an inevitability but a necessity in a world where financial transactions move at the speed of light. However, this transition must be navigated with a keen awareness of the intricate dance between operational efficiency and regulatory compliance. As the financial ecosystem evolves, so too must our approaches to safeguarding the market’s integrity. By fostering innovation in compliance technologies and strengthening collaborative oversight mechanisms, we can ensure that the move to T+1 enriches the market, enhancing both its velocity and its virtue.

In the end, the journey to T+1 offers a valuable lesson: that progress in the financial markets is not measured by speed alone but by our ability to uphold the principles of transparency, fairness, and protection that foster trust and stability. As we stand on the brink of this new era, let us move forward with both ambition and caution, ensuring that in our quest for efficiency, we do not lose sight of the values that underpin a healthy financial ecosystem.