AML Exploitation in workflows for sending or receiving

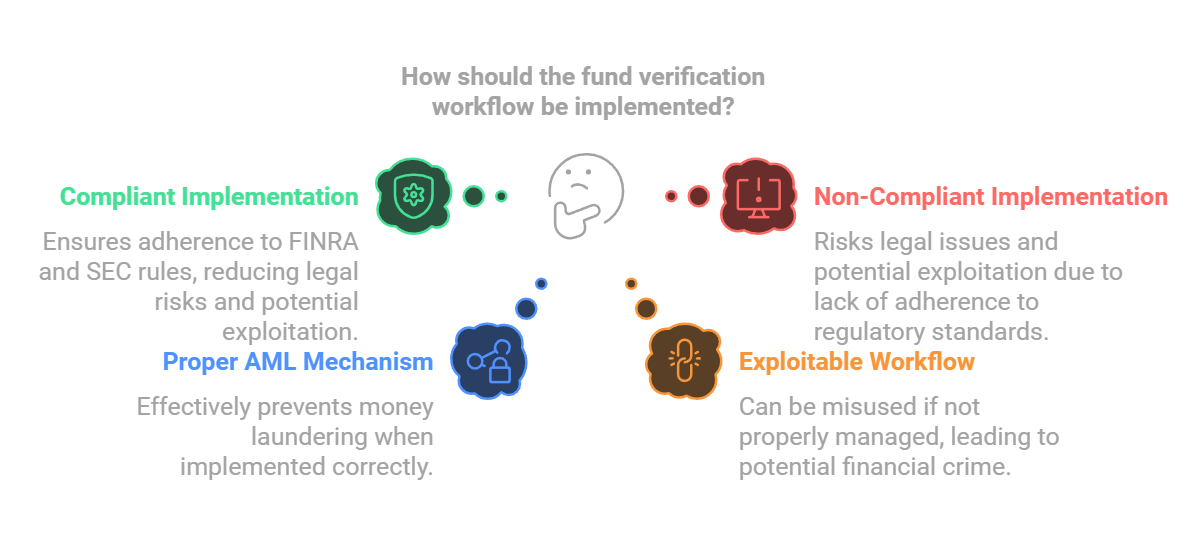

There is a workflow that Brokers use to verify funds, the workflow must be compliant with the FINRA and SEC rules.

Often that workflow is not compliant, even if it is the intent behind the original rules was not to assist in Anti-Money Laundering, however the workflow (if done properly) can be a good AML mechanism, and it can also be exploited if not implemented properly.

Exploitation can occur on Send or Receive side of these workflows related to Letters of Free Funds, where Executing and Clearing brokers send letters to Custodians to verify funds for accounts. There are a lot of ways this process can be exploited for Money Laundering. Below are several potential avenues through which Letters of Free Funds (LOFFs) workflows may be exploited by bad actors, particularly if not implemented and monitored properly. Although the original regulatory intent of these workflows may not have been to address money laundering specifically, a properly controlled and compliant funds verification process can serve as a valuable AML mechanism. Conversely, poorly managed processes open the door to abuse.

- Misrepresentation of Beneficial Owners

- Front Companies and Shell Entities: Fraudsters may use shell companies, nominee accounts, or straw parties as the account owners. If the broker or custodian simply verifies that “funds are available” without confirming the true identity of the beneficial owner, illicit funds can be funneled through seemingly legitimate channels.

- Inadequate Customer Identification Programs (CIP): If customer data is not thoroughly verified at the outset, individuals or entities can present false identification or create accounts that mask the true source of funds.

- Forged or Manipulated Letters of Free Funds

- Falsified Documentation: Criminals could attempt to present forged LOFFs to executing brokers and custodians, making it appear that accounts have the necessary funds when, in fact, they do not. If controls for verifying the authenticity of these letters are weak, illicit funds may be layered in and out of accounts without detection.

- Fabricated Authorization: Without robust procedures to validate the sender’s authority and the authenticity of instructions, instructions coming from unauthorized parties may be accepted, effectively enabling funds to move from one account to another under the radar.

- Exploiting Multiple Intermediaries and Jurisdictions

- Layering Across Multiple Brokers and Custodians: By using multiple brokers, custodians, and accounts in different jurisdictions, criminals can create complex layers of transactions. LOFFs might be passed among these intermediaries, each one verifying funds based solely on the preceding documentation rather than the underlying source, making it difficult to trace the illicit origin.

- Regulatory Arbitrage: Gaps between jurisdictions’ AML standards can be exploited. For example, a custodian operating in a jurisdiction with weaker AML enforcement might be selected to issue or receive LOFFs, making it easier to mask suspicious activities that would be flagged in stricter jurisdictions.

- Evading Transaction Monitoring and Threshold Triggers

- Incremental Funding and Transfer: Criminals might keep transfers small enough to avoid raising red flags but frequent enough to accumulate significant illicit funds. If the LOFF verification does not incorporate threshold monitoring or transaction pattern analysis, repeated small transfers may appear innocuous.

- Non-Standard Instruments or Complex Instruments: By utilizing less common financial instruments or structuring trades in a convoluted manner, bad actors can circumvent basic monitoring systems that only flag straightforward suspicious patterns.

- Weak Validation of Counterparties

- Lack of Counterparty Due Diligence: When sending or receiving Letters of Free Funds, the executing or clearing broker needs to confirm not only that funds are present but also who is providing them. If the verification process focuses purely on available balance rather than the nature of the counterparty or the legitimacy of the underlying funds, it can facilitate money laundering.

- Inconsistent Standards Among Brokers and Custodians: If one broker is stringent about verifying the legitimacy of funds but another is lax, criminals can insert themselves into the weakest link in the chain. By selectively dealing with parties known for less rigorous verification, they can exploit the process.

- Insufficient Technology and Automation

- Limited Integration with AML Systems: If the LOFF workflow isn’t integrated with AML screening tools, transaction monitoring systems, and watchlists, bad actors can more easily slip through. For example, verification letters might be accepted at face value without checking whether the associated accounts are on sanctions lists or whether recent transactions correlate with known money laundering techniques.

- Lack of Audit Trails and Data Analytics: If record-keeping is inadequate, there may be no reliable audit trail of who verified what, when, and using which criteria. Without robust audit capabilities and analytical tools, it’s challenging to detect suspicious patterns or identify gaps that criminals might exploit.

- Exploitation of Prime Broker Arrangements

- Unverified Prime Brokerage Claims: If an executing broker relies on a client’s assertion that trades will clear through a certain prime broker—without verifying prime brokerage agreements and confirming proper documentation—criminals can set up scenarios where the assumed credit or funds never materialize. This gap can allow illicit funds to appear “verified” when in reality the prime broker has not committed to the transaction.

- Delayed Reconciliation: Criminals can exploit delays or inefficiencies in confirming prime brokerage arrangements. The longer the reconciliation window, the more time they have to move funds, layer them, and obfuscate their origin.

Reinforcement of Proper Controls

Reinforcement of Proper Controls

By understanding these exploitation methods, brokers, custodians, and compliance teams can strengthen their verification processes. Proper implementation includes robust KYC, ongoing due diligence, integrated transaction monitoring, third-party validation of LOFF authenticity, thorough verification of prime broker arrangements, and consistent adherence to regulatory guidelines.

When done correctly, the LOFF verification process can serve as an effective AML checkpoint—ensuring that funds flowing through the financial system are legitimate, and that criminals face greater barriers in attempting to launder illicit proceeds.

Let’s dive into the ways just #6 in the list above can specifically be exploited. Below are a series of hypothetical, step-by-step scenarios illustrating how a bad actor might exploit insufficient technology and automation within a Letters of Free Funds (LOFF) verification workflow. Each scenario focuses on gaps that arise when verification processes rely too heavily on manual checks, outdated technology, or poorly integrated systems, rather than automated solutions that can quickly flag suspicious activity.

Scenario 1: Exploiting Manual Verification of Watchlists

Context: In a well-automated environment, every incoming instruction (including LOFFs) would be automatically screened against sanctions lists, politically exposed person (PEP) databases, and internal blacklists. In this scenario, the brokerage relies on manual lookups due to insufficient technology integration.

Steps:

- Account Setup by Bad Actor:

A criminal entity sets up a new account at a small brokerage firm under a shell company name. The initial onboarding relies on a manual KYC process with limited digital checks, missing subtle red flags about the shell company’s owners. - Submission of LOFFs from High-Risk Jurisdictions:

The bad actor initiates a done away trade and instructs the brokerage to verify funds with a custodian. They present LOFFs originating from a region known for high AML risk.- Without automated screening, the LOFF is accepted as-is.

- No Automated Screening of Source Entities:

Normally, an automated system would instantly cross-reference the sender’s name, associated entities, and jurisdictions against watchlists. Instead, a compliance officer must do this manually. Pressed for time, they do a quick but incomplete check, missing a sanctioned entity hidden behind a complex ownership structure. - Funds Are Cleared Without Flags:

Because the process relies on human judgment and there’s no automated alert, the transaction is approved. The illicit funds now appear “clean” once they settle, because no digital tool flagged the original sender as suspicious. - Repeated Exploitation:

Seeing that no automated checks are in place, the bad actor repeats the process multiple times with small amounts to stay under the radar. Without pattern recognition tools, the cumulative effect is never detected.

Scenario 2: Lack of Data Integration and Audit Trails

Context: Effective AML solutions integrate data from various sources—client profiles, transaction histories, and external watchlists—to paint a comprehensive risk picture. Here, insufficient technology means data lives in silos, with no central system connecting the dots.

Steps:

- Fragmented Systems:

The brokerage stores KYC documents in one database, transaction histories in another, and LOFF authorizations in yet another. None of these systems automatically talk to each other. - Bad Actor Initiates a Complex Web of Transfers:

A criminal group moves money through multiple accounts, each step accompanied by a LOFF from a different custodian. Because no central system correlates these trades, each LOFF verification is treated as an isolated event. - No Automated Pattern Recognition:

An automated system would notice that one entity is repeatedly involved in suspiciously similar transfers, or that funds move in circular patterns. Without automation, the compliance officer must manually review each trade, and patterns remain unnoticed. - No Real-Time Alerts:

In a modern AML setup, anomalies (e.g., too many LOFFs from a single source within a short time) would trigger automated alerts. Here, no system generates alerts; compliance teams catch issues only during periodic audits—far too late. - After-the-Fact Discovery:

Weeks or months later, during a manual audit, the firm discovers that dozens of linked transactions formed a money-laundering network. With no integrated, automated tools, the firm realizes it has facilitated illicit activities well after the damage is done.

Scenario 3: Failure to Identify Suspicious Patterns in Transaction Amounts

Context: Automated AML systems often leverage transaction monitoring rules that flag unusual sizes, frequencies, or patterns—such as structuring, where illicit funds are broken down into smaller amounts. Without this technology, illicit transactions slip by.

Steps:

- Deliberate Structuring by Criminals:

The money launderer sends multiple LOFFs, each verifying just under a reporting threshold, spread across several days. Without automation, the human reviewer might see each request as a small, innocuous transaction. - No Automated Threshold Rules:

An automated system would combine these smaller transactions and recognize a pattern designed to evade detection. Absent this, each LOFF is approved individually, as none look suspicious in isolation. - Gradual “Integration” into the System:

Over time, the launderer has verified a significant volume of funds. Without automated tracking and correlation, the pattern of incremental growth in account balances and transfers goes unnoticed. - Delayed Reporting of Suspicious Activity:

Eventually, an annual audit might find that one account frequently issued LOFFs just under key thresholds. By then, the funds may have already been withdrawn, layered, or integrated into the legitimate financial system. Real-time intervention opportunities were lost.

Scenario 4: Manual Handling of Prime Brokerage Arrangements

Context: Prime brokerage setups are complex. Without automated verification tools, ensuring that all prime brokerage documentation and approvals are in place can be difficult.

Steps:

- Complex Web of Agreements:

The bad actor claims a prime broker will settle the trades. In a fully automated environment, the system would instantly check if the proper prime brokerage agreements are on file and up to date. - Relying on Email and Spreadsheets:

Without integrated technology, the verification team checks a shared spreadsheet or emails the prime broker’s support desk, waiting for a manual response. This delay and reliance on human confirmation increases the chance of oversight or fabricated documents. - Approval Without Automated Document Checks:

Without a digital repository that alerts staff to missing or expired prime brokerage agreements, staff might sign off on a transaction believing the prime broker is backing it. - Illicit Funds Flow Through Undetected:

The launderer benefits from this documentation gap. Funds verified under the assumption of a prime broker’s involvement now enter the system with minimal scrutiny, since no automated system flagged the missing or incomplete agreements. - No Exceptions Reporting:

An automated AML solution would generate an “exception report” for any trade settled under a prime broker arrangement lacking current documentation. In the absence of such alerts, the oversight may never come to light until a regulatory examination or an internal review long after funds have passed through.

In all these scenarios, the root cause is insufficient technology and automation. Automated systems excel at pattern recognition, cross-referencing multiple data sources in real-time, and generating alerts for human teams to investigate. Without such tools, criminals can exploit gaps, rely on manual oversights, and structure their activities to slip under the radar. By understanding these exploitation methods, firms can better appreciate the value of modernizing their AML processes, integrating data sources, and implementing advanced, automated screening and monitoring solutions.

Finally, let’s look at how Prime Broker Agreements can be exploited. Below are several hypothetical, step-by-step scenarios illustrating how bad actors could exploit prime broker arrangements related to Letters of Free Funds (LOFF) workflows. Each scenario focuses on weaknesses that occur when procedures for confirming prime broker participation, validating documents, and ensuring AML compliance are insufficient or poorly enforced.

Scenario 1: Incomplete or Unverified Prime Broker Documentation

Context: Under normal procedures, an executing broker relies on a prime broker to guarantee settlement and funding for trades. Letters of Free Funds should only be considered valid if there is a confirmed and documented prime brokerage agreement in place. In this scenario, the verification process is lax.

Steps:

- Presentation of a Suspicious Prime Broker Arrangement:

A criminal entity—posing as a legitimate client—claims that all trades will clear through a particular prime broker. They provide what appear to be signed prime brokerage documents but do not supply all required pages or the latest amendments. - Lack of Automated Verification:

Instead of using a digital system that automatically checks prime broker records and flags incomplete documents, the firm relies on a manual review. Pressed for time, the operations manager skims the documents and sees a familiar prime broker’s name, assuming it is legitimate. - Execution of Trades Assuming Coverage:

Believing the prime broker will cover all obligations, the executing broker accepts LOFFs as proof of funds without probing the underlying accounts. The trades are executed and settled using the false comfort that the prime broker is backing them. - Layering Illicit Funds:

By running trades under this bogus prime broker umbrella, the criminal moves illicit funds into the financial system. Because the executing broker never confirms the authenticity or completeness of the prime brokerage agreement, there’s no immediate red flag. - Delayed Discovery:

It’s only when the prime broker later disclaims any knowledge of these transactions—perhaps during a monthly reconciliation—that the executing broker realizes it has been duped. At this point, the illicit funds may already have passed through the system and been integrated elsewhere.

Scenario 2: Impersonation or Misrepresentation of a Prime Broker Relationship

Context: A client claims to have established a prime brokerage relationship when, in fact, no such relationship exists. The executing broker’s insufficient controls and failure to confirm these claims give the criminal an avenue to launder money.

Steps:

- False Claims of Prime Brokerage Involvement:

A client opens an account, claiming that a reputable prime broker will settle all trades on their behalf. They drop the name of a well-known prime broker to gain credibility. - No Direct Confirmation with Prime Broker:

Instead of contacting the prime broker directly or checking a centralized database of active agreements, the executing broker’s team relies on the client’s word. They assume that a large, reputable prime broker’s involvement is a given. - Submission of LOFFs for Verification:

The client then submits Letters of Free Funds connected to foreign accounts or unfamiliar custodians. Without validating that the prime broker has actually agreed to stand behind these accounts, the executing broker treats these LOFFs as genuine verification of funds. - Facilitating Illicit Flows:

Under the assumption that the prime broker has done its due diligence, the executing broker does not scrutinize the source of the funds. Money flows from suspicious origins into seemingly verified accounts. The criminal effectively uses the “prime broker” façade to bypass robust AML checks. - Eventual Realization:

When the legitimate prime broker is finally contacted—perhaps triggered by unusual settlement requests or an audit—they deny any relationship with the client. At this point, multiple suspicious trades may have cleared, giving illicit funds the appearance of legitimacy.

Scenario 3: Exploitation via Outdated or Expired Agreements

Context: Prime brokerage agreements are not static; they require periodic renewals and amendments. Criminals can exploit out-of-date agreements if the firm does not have automated reminders or checks in place.

Steps:

- Initial, Legitimate Prime Brokerage Setup:

A client once had a legitimate prime brokerage arrangement with a well-respected institution. That agreement expired or was terminated months ago due to inactivity or compliance issues. - Lack of Ongoing Verification:

The executing broker does not have a system that periodically checks whether the prime brokerage agreements on file are still active and valid. There are no automated reminders to confirm renewal dates or amendments. - Submission of LOFFs Under Assumption of Coverage:

The client resumes trading activity and references the old prime broker agreement, knowing the executing broker hasn’t kept track of its current status. They submit LOFFs tied to this now-defunct relationship. - Acceptance Without Re-Verification:

The executing broker, relying on historical records, assumes that the prime broker agreement remains in place. Without automated workflows to prompt a re-check, they fail to notice that the contract is expired. - Money Laundering Through “Grandfathered” Access:

Taking advantage of this dormant but not invalidated arrangement, the criminal funnels illicit funds through trades that appear to have prime broker coverage. The aged agreement’s status isn’t questioned until a discrepancy emerges during annual reviews or regulatory audits.

Scenario 4: Complex Ownership Structures and Prime Broker “Pass-Through”

Context: A criminal entity sets up multiple shell companies and claims that their prime broker arrangement covers all subsidiaries and affiliates. Without automated systems to verify the chain of ownership and the prime broker’s explicit coverage, confusion and exploitation arise.

Steps:

- Multi-Entity Setup:

The criminal creates a web of companies, some in high-risk jurisdictions. The main entity lists a prime broker arrangement in its documentation. - Assuming Broad Coverage:

The criminal then uses Letters of Free Funds from other shell companies within this network, implying that these entities are also covered by the prime broker because they are “affiliated” with the primary client. - No Hierarchical Verification:

Without systems that automatically check whether the prime broker arrangement explicitly covers all related entities, the executing broker applies the original prime broker relationship to the entire network. - Layering Through Multiple Accounts:

Funds move through various shell accounts, each time appearing to be validated by the prime broker arrangement. Since the executing broker doesn’t verify each entity’s standing, the criminal launders money by piggybacking off a single, possibly out-of-scope prime broker agreement. - Discovering the Gap:

Eventually, a suspicious transaction triggers a manual review. The firm realizes that the prime broker only had an agreement with the primary entity, not the chain of affiliates. By then, layers of illicit funds have passed undetected.

Conclusion:

These scenarios underscore how criminals can exploit prime broker arrangements when firms lack rigorous verification processes, automated checks, and ongoing monitoring. By ensuring direct confirmations with prime brokers, maintaining up-to-date documentation, and integrating technology solutions that automatically verify and re-verify coverage, firms can better prevent these forms of abuse. Proper controls turn the prime brokerage relationship into a reliable AML checkpoint rather than a vulnerability.